Justice Clarence Thomas asked a rare question in racial bias case -- here's why

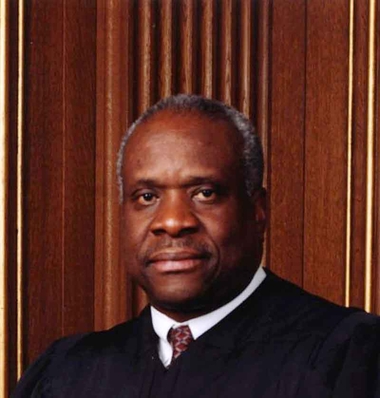

The question Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas asked on Wednesday -- one of his exceptionally rare queries -- involved race. But as has happened before, there was a twist.

Thomas, only the second African-American justice in US history, has gone for years at a stretch without asking a question, including a full decade, from 2006 to 2016. On the occasions his voice has been heard, it has often related to race but with a counterintuitive thrust, as occurred in the new dispute over a Mississippi prosecutor's repeated elimination of blacks from a jury pool.

Thomas has given many explanations for his singular silence through the years, including that he believes the justices should give the lawyers at the lectern more time to present their cases. He earlier referred to his youth in Pin Point, Georgia, where he developed a dialect he said was mocked; Thomas has said that gave him the habit of listening more than speaking.

Thomas employs a distinct conservative approach that puts him on the far right of the generally conservative Supreme Court and in the exact opposite place of the man he succeeded in 1991, Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American justice.

He opposes governmental racial remedies across the board. He has voted against campus affirmative action and electoral districts drawn to enhance the voting power of minorities who have long faced bias at the polls. The latter issue of "majority minority" voting districts spurred a few questions from him in the 1990s.

Thomas believes the Constitution's equal protection guarantee forbids such racial measures and, in a practical vein, argues that they stigmatize blacks, Latinos and other racial minorities.

Most importantly related to Wednesday's case, Thomas has narrowly interpreted the protections of a 1986 milestone decision, Batson v. Kentucky, intended to prevent prosecutors from using peremptory challenges to strike potential jurors based on their race. (Each side at trial is accorded a set number of such challenges that allow the elimination of jurors without any reason; however, the strikes cannot be based on race or gender.)

Three years ago, Thomas was the lone dissenter when the high court ruled against prosecutors in Georgia who had systematically kept blacks off a jury. Thomas believed the high court should have deferred to the state judges who handled the case, and he brushed aside evidence the defendant's lawyers had found of prosecutors' notations identifying jurors to be struck by their race.

Wednesday morning, Thomas again went against the emphasis of the majority as he abandoned his usual reluctance to enter the fray.

On Wednesday, most of the justices expressed concern about a prosecutor with a history of discriminating against black jurors who had been called for the murder trial of Curtis Giovanni Flowers. The question was whether he had engaged in the practice yet again, at Flowers' sixth trial. Flowers, an African-American, was convicted and sentenced to die for the 1996 killings of four people at a furniture store in Winona, Mississippi.

"The only plausible interpretation of all the evidence viewed cumulatively is that (prosecutor) Doug Evans began jury selection in Flowers VI with an unconstitutional end in mind," said Flowers' lawyer, Sheri Lynn Johnson, "to seat as few African-American jurors as he could."

Justices across the ideological spectrum were open to her arguments. Justice Samuel Alito referred to the "troubling" history of earlier instances in which the prosecutor had been found to have violated the principles of Batson, based on his screening of black jurors. (Flowers' murder convictions from the first three trials were thrown out. Two of his trials ended in hung juries. At issue is his sixth trial from 2010, in which a jury of 11 white people and one African-American found him guilty of four counts of murder.)

Thomas, at the very end of the hourlong hearing, suddenly spoke and essentially turned the tables by asking Johnson about the use of peremptory challenges by the defense team, not the prosecution.

"Ms. Johnson, would you be kind enough to tell me whether or not you exercised any peremptories ... were any peremptories exercised by the defendant?"

"They were," Johnson responded.

"And what was the race of the jurors struck there?" Thomas asked.

Referring to Flowers' trial attorney, Johnson said: "She only exercised peremptories against white jurors. But I would add that ... her motivation is not the question here. The question is the motivation of Doug Evans."

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the court's only Latina justice, interjected, suggesting that the defense lawyer could not have eliminated any blacks because the prosecutor had already removed virtually all from the pool.

"She didn't have any black jurors to exercise peremptories against -- except the first one? ... After that, every black juror that was available on the panel was struck?"

"Yes," Johnson said.

Thomas asked nothing more.

By Joan Biskupic, CNN legal analyst & Supreme Court biographer. The-CNN-Wire™ & © 2019 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.

The Gayly – March 20, 2019 @ 4:25 p.m. CDT.