What the March on Washington did for the LGBTQ+ Rights movement

And the tenacious gay leader who fought for change

- by Robin Dorner

Editor in Chief

On an August morning in 1963, as the summer sun rose over the National Mall, a crowd numbering a quarter of a million gathered in unity, their voices swelling with hope for justice.

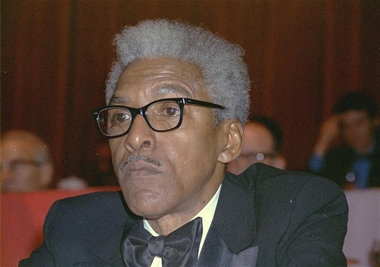

At the heart of this historic convergence—the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—stood Bayard Rustin, a man whose genius and tenacity orchestrated one of the most consequential days in American history.

Rustin was an American civil rights activist and key adviser to Martin Luther King, Jr. He was the main organizer of the March on Washington in 1963, and he was openly gay.

Born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1912, Rustin’s Quaker upbringing instilled in him a fierce commitment to nonviolence and equality. Those ideals would propel him from local protestor to international organizer, though his journey was anything but simple.

As an openly gay Black man, he worked mainly in the shadows—his sexuality regularly weaponized by critics hoping to silence his impact. Yet those who met him saw a visionary: a key advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., a strategist who introduced nonviolent resistance to the civil rights movement, and above all, a relentless advocate for dignity.

In 1953, Rustin was arrested in California after he was discovered having sex with a man. He served 50 days in jail and was registered as a sex offender.

Ten years later, the March on Washington, which Rustin masterfully engineered, was more than a call for racial justice. It was a symphony of difference, a coalition of Americans demanding that the nation fulfill its promise for all its citizens. The event’s triumph, crowned by Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, set the stage for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But Rustin’s legacy extended well beyond these bills.

As Rustin moved quietly among leaders and laborers alike, his eyes were fixed on a broader horizon. He envisioned a society where divisions of race, class, gender, and sexuality could be overcome—where “we are all one,” as he often said.

He built a template for organizing the march—coalition-building, peaceful demonstration, and intersectional solidarity—and this would become the backbone for future movements, including those for LGBTQ+ rights.

Though rarely recognized during his lifetime as a champion for gay rights, Rustin’s approach at the March on Washington never lost sight of inclusion. LGBTQ+ activists, many of whom long faced systemic barriers, drew inspiration from Rustin’s methods.

His strategies honed on the Mall—mass mobilization, alliance formation, and unyielding advocacy—echoed in the fight to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” in campaigns for marriage equality, and in every march demanding justice for all identities.

Imagine promoting an event like this without social media. It took the strategic and tactical acumen of a man like Rustin.

Today, the spirit of the march endures. Rustin’s belief that progress for one group strengthens the rights of all now shapes every new chapter in the ongoing struggle for equality.

The Mall, once filled with dreamers and believers, continues to be shaped by the legacy of a man who, despite being forced to the margins, built the framework for lasting change. In remembering Bayard Rustin, we remember that every march forward began with a step taken together.

In 2013, Rustin was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 2020, Rustin was pardoned for his 1953 conviction.

Rustin died on August 24, 1987, in New York City, New York. He was 75 years old.

The Gayly online. 1/23/26 @ 11:56 a.m. CST.