What would a 'Medicare for All' policy mean?

If you've been watching the Democratic presidential hopefuls gear up, you have probably heard the phrase "Medicare for All."

What exactly does that mean?

Medicare, which has been around since 1965, is the government-run health insurance program that covers all Americans 65 and older and is funded by taxpayers. A portion taken out of our paychecks for Social Security goes toward Medicare to cover most services like hospital stays and doctors' visits.

People on Medicare can also choose to get additional coverage from Medicare-approved private insurers to cover other services such as dental, vision and prescription drugs.

Proponents of Medicare for All want to expand this program to cover more than just Americans 65 and older. Some, such as Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, are pushing for Medicare to cover all citizens and lawful permanent residents, while others such as Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow are pushing to lower the age requirement. In 2017 she introduced a bill to allow people between 55 and 65 years old to buy into the program. Earlier this year Stabenow introduced another bill further lowering the age requirement to 50.

RELATED: Fact-checking the first night of the first Democratic presidential debate

Many of those pushing for Medicare for All believe that health care is a human right, and many supporters believe that getting more people into the Medicare system can help rein in growing costs in the US health care system.

It's worth noting that Medicare is quite popular as it stands now. In a Gallup poll from December, of those Americans publicly insured through Medicare or Medicaid (the government's health program that covers those with limited income), 79% say they are happy with the quality of their health care and believe that they have good to excellent health coverage.

Where did this idea start, and why is it gaining traction?

The concept of a government-funded health care system isn't new. Efforts to provide some sort of universal health coverage in the United States date all the way to 1904, when the Socialist Party endorsed the idea.

In 1912, Republican President Theodore Roosevelt ran for a third term as a Progressive Party candidate; his platform included a "single national health service." Even though he lost, the concept of a single-payer system would continue to make its way into political discussion. Some of the strongest resistance to a nationalized health care system came from physicians who feared that it would interfere with their profits.

Teddy's cousin President Franklin Roosevelt would try to pass a universal national health insurance program as part of the Social Security Act in 1935, as part of the New Deal. President Harry Truman continued to push for it during his time in office. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, fear of socialism and a panic by Southern Democrats that a nationalized health care system would require desegregation ultimately thwarted the health care efforts.

It came back to prominence when Sanders included it as part of his 2016 presidential platform. He didn't win, but the idea took off with a number of Democrats. In fact, it also has some support from Republicans. According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll, 40% of Republicans support the idea of federally provided health insurance.

In September 2017, Sanders and 16 Democratic co-sponsors introduced a Medicare for All expansion bill to cover all Americans. The co-sponsors included California Sen. Kamala Harris and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who are running for president in the 2020 election. In April this year, Sanders reintroduced the bill alongside 14 cosponsors, including Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Kirsten Gillibrand, who are also seeking the Democratic nomination for president, as well as Harris and Booker.

Theirs wasn't the only bill to try to expand Medicare. In the last congressional session, there were at least eight other proposals introduced in the House and the Senate aiming to expand the program. Some would have expanded the program by lowering the Medicare age eligibility to 50; other bills added a Medicare option while maintaining private insurance choices.

Last summer, Democratic Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington helped found the Medicare for All Caucus, which now has 78 Democratic representatives as members.

What would the program do?

Our health care system could best be described as a hybrid. About half the money comes from the private sector: people who have private insurance through their employers or who are self-insured. The other half is from the public sector: federal, state and local governments paying into Medicare and Medicaid.

If the country adopted Sanders' proposal, people who currently get their insurance from their employers would move to the government system. Sanders' plan would provide fairly comprehensive coverage, as Medicare does now, all with no copays, premiums or deductibles. It would include inpatient and outpatient hospital care, emergency services, preventative services, most prescription drugs, as well as dental and vision coverage. His 2019 plan also covers long-term or nursing home care. The only potential for out-of-pocket fees would be for some prescription drugs and certain elective procedures.

If states wanted to fund additional benefits for their residents, under the Sanders proposal, they could, but they would have to do so without federal assistance.

Aside from getting more people access to health care, supporters of Medicare for All say that moving to this system would create efficiencies to help bring down costs of health care. The US health care system now costs nearly double what other high-income countries pay, per capita.

Under Sanders' plan, would I be able to keep my doctor?

As long as your doctor is state-licensed and a certified Medicare provider, your visit would be covered. But if your doctor chose not to participate in Medicare, you would have to either pay out of pocket or see a participating doctor.

What wouldn't the program cover?

Under the comprehensive Sanders program, the only things you would probably have to pay for would be certain elective and cosmetic procedures. It could eliminate much of the private insurance system as we know it. Private plans could exist to cover the few procedures not included in the plan.

Other proposals aim to keep the private insurance system and add an expanded Medicare or public option.

Also, keep in mind that Medicare pays doctors and hospitals less than private insurers for services, and not all hospital systems or doctors accept Medicare. The American Hospital Association found that private health plans pay hospitals about 45% more than treatment costs, while Medicare and Medicaid pay about 12% less than costs, a difference of 57 percentage points If we moved to a Medicare for All system, would all hospitals and doctors agree to this pay cut? Would they organize to demand more? These are the kind of questions that architects of an expanded system have to wrestle with.

If Sanders' Medicare for All were to become law, it wouldn't happen overnight. It would roll out over four years.

In the first year, Medicare would grow, with the eligibility age dropping to 55 and with all children 18 and younger added to the rolls. Over the next two years, the age would drop to 45 and then 35. By the fourth year, it would truly become "Medicare for all."

How would this be paid for?

This is where the rubber hits the road and one of the reasons it's such a contentious issue.

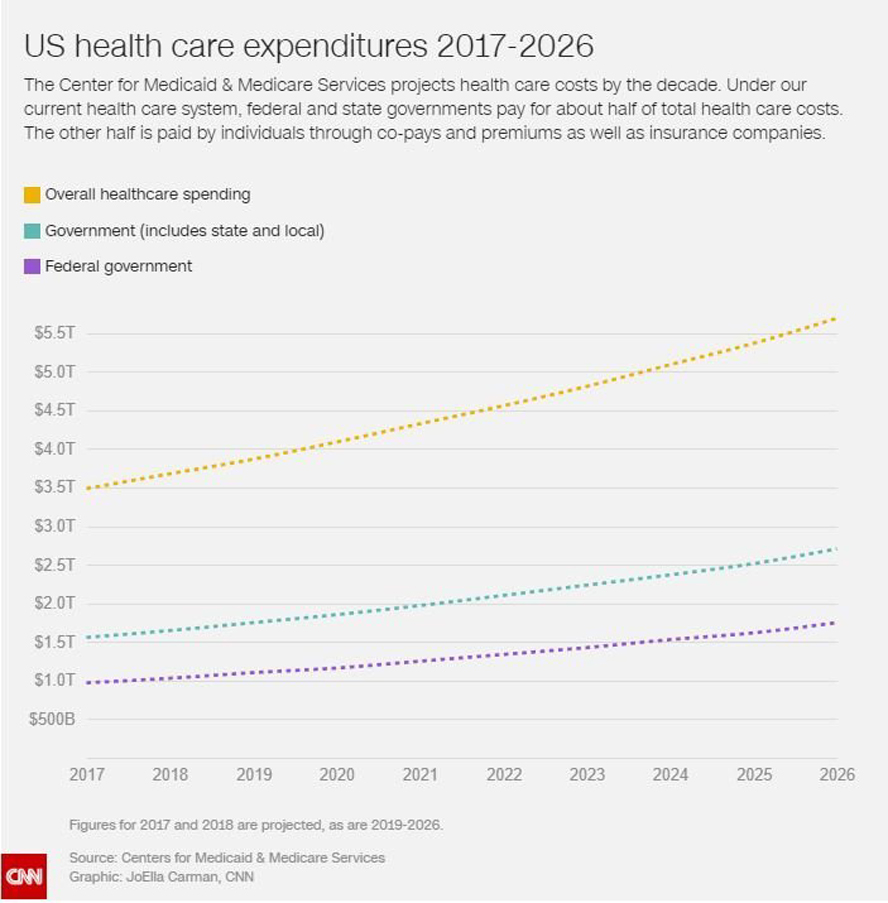

The graph below illustrates the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' projections for health care spending from 2017 to 2026.

There are several numbers to consider when we think about health care costs.

1. National health care spending: That's the yellow line in the graph. It represents how much we as a country spend on things like drugs, doctor's visits and hospital care; including all sources of funding, both public and private. In 2017, the cost of health care was $3.5 trillion. Over the decade from 2017 to 2026, the cost is expected to be $45 trillion.

2. Federal health care spending: This purple line represents the federal government's share of national health care spending, which includes Medicare and Medicaid. Much of this comes from taxes. In 2017, federal health care spending was $974 billion. Over 2017 to 2026, federal health care spending is projected to be $13 trillion.

3. Total government spending: That's the green line, federal health care spending plus what states and local municipalities pay. It represents about half of total national health care spending; the other half comes from the private sector. In 2017, total government spending was $1.56 trillion. Over the decade from 2017 to 2026, total government spending is projected to be $21 trillion.

Sanders' Medicare for All plan analysis

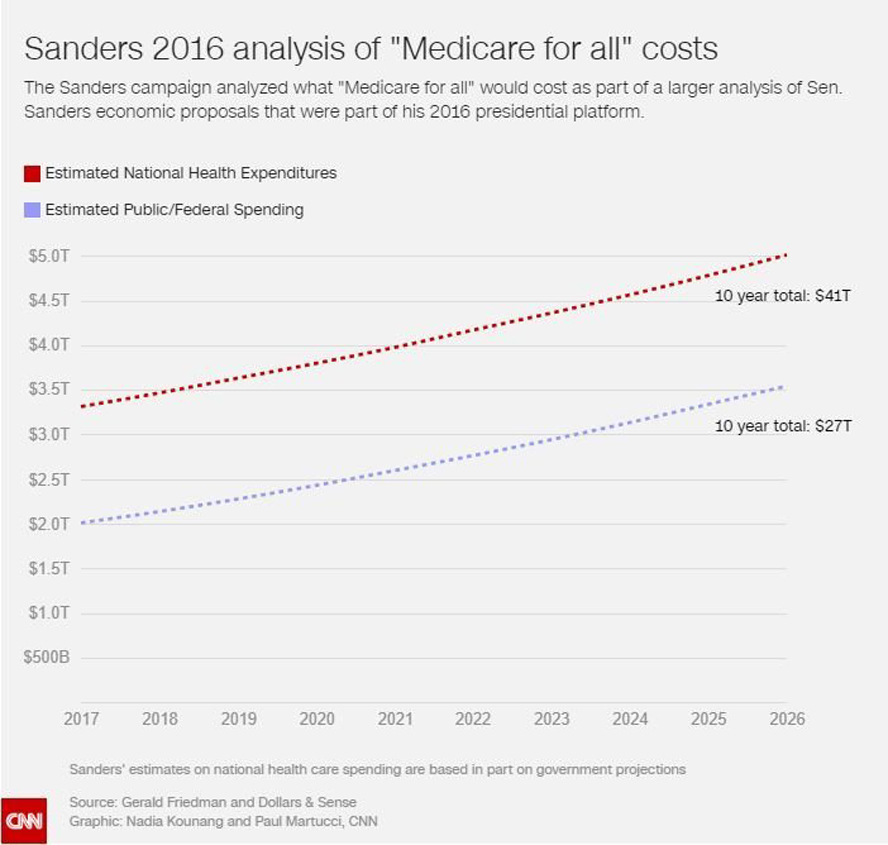

Sanders' analysis was based on the initial Medicare for All proposal he ran on in the 2016 campaign, which did not include coverage for long-term care. That analysis used 2016 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services health expenditure projections. Sanders' 2019 proposal doesn't detail exactly where money will come from, or how much it will require, but his office did suggest some potential options, which focused on more progressive taxing.

To get the clearest economic picture of how to pay for this, CNN used Sanders' 2016 assumptions and applied the same savings ratios to the most current projections in this analysis of Sanders' data.

1. National health care spending: Using Sanders' assumptions, under Medicare for All, national health care spending for 2017 would have been just about $3.2 trillion. Over the decade from 2017 to 2026, Sanders' total national health care spending would have been close to $39 trillion.

Keep in mind that Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services projected that national health care spending under our current system is about $45 trillion from 2017 to 2026. If Sanders' assumptions are correct, Medicare for All would lower national health care spending by about $6 trillion over the decade.

Sanders believes that those savings would largely result from reduced administrative costs, reduced payments to physicians and lower prescription drug prices resulting from a single-payer system.

2. Government spending: Sanders doesn't make a distinction between federal and state spending in his analysis. All of his spending is considered federal or public since, under the Medicare for All plan, the federal government is largely the single-payer.

Sanders' analysis assumes that if Medicare for All had been implemented in 2017, in that year, federal spending would have been approximately $2 trillion, and total public or federal spending would have been about $27 trillion for the decade 2017-26. But again, Sanders estimates that total national health care spending under Medicare for All would have hit $3.2 trillion for 2017 and about $39 trillion over the decade, meaning Sanders still would need an additional $12 trillion to $14 trillion to cover national health care spending for the decade.

To pay for the newest version of his plan, Sanders has suggested several potential options, which his office listed as:

• Creating a 4 percent income-based premium paid by employees, exempting the first $29,000 in income for a family of four

• Imposing a 7.5 percent income-based premium paid by employers, exempting the first $2 million in payroll to protect small businesses

• Eliminating health tax expenditures

• Making the federal income tax more progressive, including a marginal tax rate of up to 70 percent on those making above $10 million, taxing earned and unearned income at the same rates, and limiting tax deductions for filers in the top tax bracket

• Making the estate tax more progressive, including a 77 percent top rate on an inheritance above $1 billion

• Establishing a tax on extreme wealth

• Closing the "Gingrich-Edwards Loophole"

• Imposing a fee on large financial institutions

• Repealing "corporate accounting gimmicks"

Sanders argues people would save money because they would no longer have to pay copays, monthly premiums or deductibles.

Some experts believe that Sanders' picture is too rosy, overestimating how much savings would result from the single-payer system.

Critics also worry that he has underestimated the increased cost from more people using health services. There are now about 28.5 million uninsured Americans, and it shouldn't come as a surprise that providing insurance for that many more people will be expensive.

A recent Pew Research Center poll found that 6 in 10 Americans believe that it is the federal government's responsibility to make sure all Americans have health care coverage.

The left-leaning Urban Institute estimated that, over the same 10-year period, under the Sanders plan, national health care spending would increase by more than $6 trillion over what we are projected to spend by 2026. It also projected that national health care spending would be closer to $51 trillion, instead of Sanders' projection of $41 trillion. That means an additional $32 trillion in new federal spending, according to the Urban Institute's estimate.

Other experts, including Kenneth Thorpe, chair of health policy and management at Emory University's Rollins School of Public Health, also take issue with Sanders' estimates. No matter how the cost is cut, everyone will be affected, Thorpe said, and Sanders' proposed tax hikes couldn't cover the $32 trillion increase.

Thorpe believes that sales taxes would have to increase, on top of the other tax hikes Sanders has called for, to get to the needed $32 trillion. And that would affect everyone. Sales tax is a regressive tax, meaning it will affect the poor more than the rich.

Thorpe knows this not just because he's an economist and has analyzed Sanders' 2016 plan but because he was chosen by the Vermont legislature in 2005 to analyze potential blueprints for a single-payer system in the Green Mountain State.

"There will be winners and losers," he explained. And who may end up paying more might surprise you.

According to Thorpe, someone already on Medicare or Medicaid who is paying very little, if anything, in premiums would probably start paying more taxes and potentially see no relief, or offset, on premiums. The reason is that what they are paying in taxes is potentially greater than their current premiums.

Small-business owners could be in a similar boat. If they have fewer than 50 employees, they are currently not paying premiums for their employees. But they would pay more in payroll taxes and not see any relief, or offset on premiums.

Are there other places that do this?

Canada and Taiwan are often cited as examples of other places that have single-payer health care systems under which all residents are insured. Those governments pay for health care through taxes on their citizens. In Canada, the federal government provides only health care, and dental, vision and prescription drugs may be covered by the province or through private insurers.

Britain's National Health Service is also often used as an example of a single-payer system. But in the English system, the government not only pays for services, it contracts with and employs doctors and hospitals directly. This is considered socialized or nationalized health care.

In Canada and Taiwan, and under Medicare in the United States, the government doesn't own or contract the providers. The British system is more akin to the US Veterans Administration.

Another country that frequently comes up as a model in the health care debate is France, which has a mix of public and private insurance. Although most of France is covered by one of the three not-for-profit health insurance funds financed by the government and covers between 70% and 80% of costs, there are private supplemental insurers, as well.

All of these countries provide almost universal health care, through which insurance is either provided or mandated by the federal government.

Why is health care so expensive in the first place?

In the United States, for every one doctor, there are about 16 staff members -- but only six of those staff members actually have clinical roles, like nurses' aides or medical assistants.

That's more than $800,000 in labor costs per doctor. Unlike in countries that have a nationalized or single-payer system, the United States has hundreds of health insurance providers, with different codes and different rates all for the same procedures. It's administratively inefficient if the same knee replacement can be processed and charged in dozens of ways.

The cost of lifestyle diseases, such as obesity, is staggering in the United States. There are estimates that 80 percent of diabetes, heart disease and stroke and 40 percent of cancer cases are preventable. By 2050, as many as 1 in 3 US adults are expected to be diabetic.

We also spend way more on technology and drugs. Pharmaceutical drugs are particularly costly in the United States, partly because the largest user of prescription drugs -- Medicare -- can't negotiate prices down with drug manufacturers. Under Sanders' plan, the government would come to the table to broker pricing.

Patients in the US health care system tend to have a lot more unnecessary tests and procedures than patients in other countries, and that all adds up to a high price tag. It's in part due to profit motivation, as well as a phenomenon known as "defensive medicine." That's when doctors and hospitals are overly cautious and perform tests and scans out of fear of ending up out of the operating room and in the courtroom. In 2008, defensive medicine cost the United States $55.6 billion in health care costs.

According to the nonprofit National Academy of Medicine, in 2009, one-third of all health care costs was a complete waste and did nothing to make Americans actually feel better.

What do most people think about Medicare for All?

This proposed expansion isn't just popular with politicians; it has a lot of support from their constituents. A CNN poll from July 1 found that 56 percent of Americans support a national health insurance program for all Americans, even if it would require higher taxes. An earlier Kaiser Family Foundation survey from January found that 56 percent of Americans support Medicare for All.

Public support also depends how you qualify the program. Remind people that it will eliminate health insurance premiums and reduce out-of-pocket health care costs for more Americans, and according to a January Kaiser Family Foundation survey support for the program spikes to 67 percent. If you tell people that Medicare for All guarantees health care as a right for all Americans, approval for the program jumps to 71 percent.

But remind them that it could eliminate private insurance, and support flips. According to the CNN poll, 57% of respondents said that a national health insurance program should not completely replace private insurance.

In the meantime, what can I do to lower my own health care costs?

Take control of your health. Eat better. Exercise.

Chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes and obesity are among the most prevalent and costly in the United States. Six in 10 Americans has at least one chronic disease; 4 in 10 have two or more. Americans with five or more chronic conditions make up 12 percent of the population but account for 41 percent of total health care spending. These Americans spend 14 times more on health care than those with no chronic conditions.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, chronic diseases account for 90 percent of all health care spending. These conditions are the leading factors of our nearly $3.5 trillion in health care spending.

By Dr. Sanjay Gupta, Chief Medical Correspondent via The-CNN-Wire™ & © 2019 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.

The Gayly 7/2/2019 @12:25 p.m. CST.