Building the resistance - #OrlandoStrong

by Robin Dorner

Editor in Chief

It was a balmy June night in central Florida in 2016. Friends gathered in Orlando to enjoy a night out of fun and conviviality. The Pulse nightclub was open for business. Drinks were flowing and the salsa music was playing. It was Latin night in the club.

It was Sunday night. Ricardo Negron-Almodovar was in the Pulse Nightclub enjoying the company of friends.

That night a gunman chose to victimize clubgoers and turn Pulse into the site of a bloody massacre, forever changing the lives of victims and their families.

“When I posted that [I was in the club] on my social media, I was contacted by so many media organizations,” said Negron-Almodovar. “It can get so draining. It was three or four in the morning. Somehow, the media got my number or they would call through the messenger app. I had to turn off my phone because it became overwhelming. It was just too much. It was honestly too much.

“When you are going through all that, we don’t care about being a source, your assignment or your deadline.”

That night, 49 people were killed and 53 were injured in this terrorist attack/hate crime. The gunman was shot and killed by police after a three-hour standoff.

This massacre is both the deadliest mass shooting and the deadliest incidence of violence against LGBTQ people in US history.

Negron-Almodovar said some of them exited through the backside of the club. That’s how he escaped.

“Those were the first 24 hours. Immediately it became visible that there was a language barrier. Between who was providing stories to the media and how the narratives actually made it out. We saw that more of the stories of the white people made it out into the news media because of the language barrier.

“We forgot all about the intersectionality of all of it. That in and of itself brought up so many issues. Seeing media clips is how some families found out they [people in club] were gay. One man said if his family found out he was gay, he may as well be the 50th victim because his family would kill him.”

After the tragedy, Negron-Almodovar said people were engaging in a lot of risky behavior to cope with the tragedy. Risky behavior like alcohol abuse, drug abuse and unprotected sex. He said [STD] infections have gone up 33 percent.

Negron-Almodovar says there’s no ‘moving on.’ At least not for those directly involved.

“So where do we go from here? Once the cameras are gone, we are still here. There are many people who have not yet gotten their visas even as a victim of crime. So, going on from this we have to make sure all intersections represented from this are included. We have to understand that while there is a big story, there are still these underlying stories that go on. We have to pick up the pieces and keep going,” he said.

In another part of Orlando, Erik Sandoval of CBS Orlando got a call from his news director. “I need you. We have another nightclub shooting.” Sandoval called the assignment desk and found out it was Pulse and headed that way.

“As I got closer, I saw helicopter in the sky and mass police presence,” said Sandoval. “There was to be a press conference in a parking lot and no one ever showed. We knew at this moment, this was bigger than we realized.

“We were all waiting around and suddenly, we heard loud shots of gunfire. We didn’t know if this was the gunman or police.” Of course, this would be the shots that rang out when the police shot the gunman.

Billy Manes with Watermark, Central Florida's LGBTQ newspaper, said he was awakened by his husband telling him something had happened. “No one really knew what had gone down. I knew I had to change the paper [going to press]. It was jarring, but at the time you didn’t think about it. You just knew you had a job to do.”

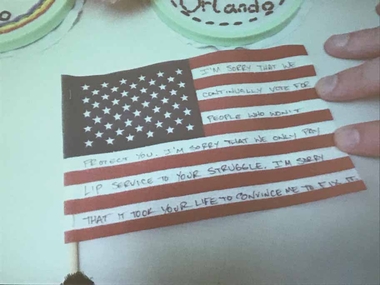

“Before long we knew this was terrorism of some sort: A hate crime,” added Manes. “I was very focused on the fact that this was a huge blunt to our gay community. After all the rights and almost a year after marriage equality. There we were basking in it and suddenly we have 49 bodies down there.

“I have learned more than I have ever known is that you have to be there now. I don’t think any of us have recovered [a year later]. We have an infrastructure built within the women’s groups, groups like Black Lives Matter and we can pull from these resources because we are all in the same fight.”

These LGBTQ journalists had to deal with the fact they may know someone in the club, none-the-less having to report on it professionally.

Last month, plans were announced to build a permanent memorial and museum on the building’s grounds to honor the victims. The OnePulse Foundation will begin raising funds for that cause.

“There’s so much we can’t cover with a mass death like this,” Manes exclaimed. “You can’t cover all the pain. I think it makes it different in this social construct. There are topics that people don’t want to broach.”

“Declaring it a hate crime or a terrorist act is important,” Sandoval said. He spoke to the insurance agent for the club. “If it’s a hate crime, the insurance will pay. If it’s a terrorist attack they won’t,” he said.

According to LGBTQ Orlando, there is a huge sense of moving forward.

#OrlandoStrong #KeepDancingOrlando

Copyright 2017 The Gayly – June 12, 2017 @ 10:30 a.m.